70 Little’s Triangle

- Dave Goble

- Jun 13, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Feb 28, 2024

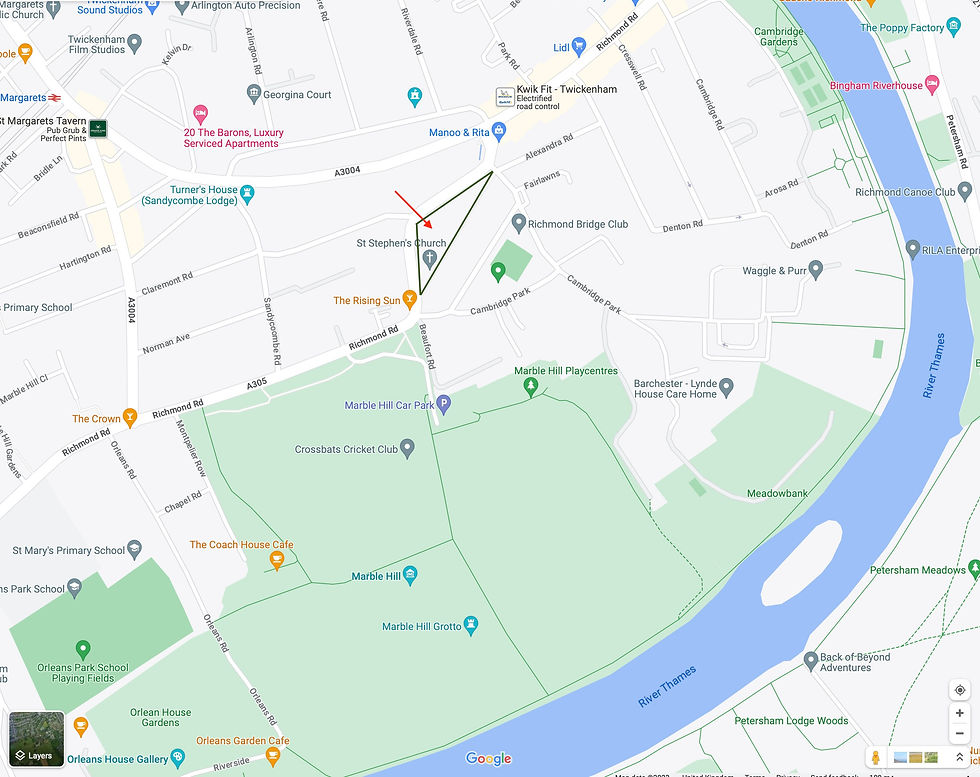

The theme of expansion for places of worship to accommodate a growing population on the back of an extending rail network has threaded its way through a few posts to date. It continues here in the story behind St. Stephen’s Church, built with capacity in mind, and so dwarfing the nearby chapel it was to replace in East Twickenham, to be located on a triangle of land contained by Richmond Road and an ancient right of way known as St. Stephen’s Passage.

In 1720, having retired from the army, Captain John Gray bought land in the area, near the river, to build homes for the “respectable citizens of Twickenham”. I can’t help but wonder what that means, and in particular who it excludes. Anyway. He named it Montpellier Road, and wanted it to have its own chapel and school to serve the householders, their families and staff. Obtaining approval from the Bishop of London, Gray built Montpellier Chapel with a capacity of 250, and appointed his own chaplain. An engraved communion plate from 1720 commemorates the opening of the chapel, and is now held by St. Stephen’s Church.

Leaping forward in time almost 130 years to 1848, the railway had reached Twickenham. Just 25 years later in 1873 local residents decided to petition for a station nearby at St. Margaret’s, a key supporter being local builder and developer Henry Little, who had begun developing land around his home at Cambridge Park House for professionals including bankers, lawyers and business owners who fancied moving to outer London. Hmmm ... these folk sound like they may have qualified as the respectable folk of Twickenham referred to earlier by Captain Gray.

In the meantime the arrival of the railway had the familiar and predictable effect of expanding the population, and in recognition of the fact Montpellier Chapel was too small to cope, an appeal was launched in April 1873, (a busy year), to raise the £7,000 required to build a church with a capacity for 1,000 people, four times that of the chapel. That sum of money would be about £7m today, and astonishingly the full amount was surpassed in less than six months, by August that same year. The Little family donated the aforementioned triangle of land, and architects Lockwood and Mawson, previously known for their work on the model community of Saltaire in Yorkshire, were commissioned. A new parish was divided off from Twickenham, and The Duchess of Teck (the larger than life mother-in-law of the future George V) laid the foundation stone.

By December 1st 1875 the foundations for the entire church were completed, but only the nave was ready for consecration. It would be another 32 years, in 1907, before consecration of the tower by the first Bishop of Kensington marked completion of the external structure. The first Vicar of St. Stephen’s church was Rev Francis Moran, who had been the minister at Montpellier Chapel. Henry Little maintained his involvement, becoming the first People’s Churchwarden.

In 1876 the church became operational, and the Montpelier Chapel was sold for use by various secular businesses, finally collapsing in 1941 after which it was replaced by a house. Stones from the chapel arched windows were taken to St. Stephen’s, and in 2011 used to make a bench outside the new extension. The school building Gray Built is now a private house, incorrectly named ‘The Old Chapel’.

South facing entrance (west facing if St. Stephen’s was correctly oriented)

A chapel was built on the northern edge of the parish by St. Stephen’s in 1896. This was to serve the residents of the workers’ cottages in the area, between Winchester Road and the Chertsey Road. The building is now used by St. Stephen’s school, which was built at the same time.

To mark the anniversary in 1976 of the opening of the church, the Centenary Room was created from the West (South) door entry area. A new building called the Crossway was opened in 1999 for use by the community and the church, with an extension to the church called the Spring being built alongside St. Stephen’s passage, which was opened by the Bishop of Kensington, Paul Williams in 2011. In 2013 the Ark Room (old choir vestry) was transformed into a chapel space called the Prayer Chapel.

St. Stephen’s Church interior boasts some fine features, including examples of Victorian stained glass by Alfred Octavius Hemming, and the tops of stone columns decorated with carvings of flowers based on plants found in Henry Little’s garden. Below the clerestory windows, the church’s Evangelical tradition is commemorated by stone carvings of the heads of the key leaders of the Reformation: namely Wycliff, Cranmer, Latimer, Ridley, Bradford and Hooper. To cap it all, installed in 1889, the church has one of the best preserved Henry Willis & Sons organs in London. It is Grade II listed, and the current Vicar is Jez Barnes.

South facing (west) entrance

North facing (east) alter end

I should explain the conflicting compass point references that weave through this post. Constraints imposed by the size and shape of the site where the church sits are responsible for it facing north rather than east, which is the usual ecclesiastical layout. More at the end on this.

Inside, looking north (east)

Orientation in church architecture (sorry, but it piqued my interest).

Since the eighth century orientation in church architecture has placed the point of main interest in the interior towards the east, where the alter is located, often within an apse. The façade and main entrance are accordingly, (usually), at the west end. Even in the many churches where the altar end is not actually to the east, terms including ”east end", "west door" and “north aisle" are commonly used as if the church were correctly oriented, treating the altar end as the liturgical east.

There are a number of theories regarding the significance of orientation in church architecture. Early Christians faced east when praying, probably related to the ancient Jewish custom of praying in the direction of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. Some non-Christians thought they worshipped the sun. Various other mystical reasons have been put forward to account for the custom, including anticipation that Christ's Second Coming will be from the east: "For as the lightning comes from the east and shines as far as the west, so will be the coming of the Son of Man".

It’s not uncommon to find a church building failing to comply strictly with liturgical direction, with geographical / physical constraints often necessitating compromise for parish churches as we have seen here, and even cathedrals.

What about that whiff?

Before closing, after checking the Timeline that accompanies these posts I want to mention something that on reflection I’m surprised hasn’t cropped up in my research into St. Stephen’s Church: That whiff of cabbage that agitated Tennyson’s nostrils to distraction in the early 1850s. He lived just south of here, a few hundred yards down the road in Chapel House on Montpelier Row. He upped sticks and left Twickenham for the Isle of Wight. The area where St. Stephen’s is located would not have escaped said whiff, being similarly downwind of the source - the cabbage patch – just like Chapel House. It doesn’t seem to have got up the hooters of any of the congregation there, or the “professionals” lauded by Mr. Little. Or if it did then perhaps they were all too "respectable" to mention it.

Many of them presumably grew up with it, and may have become accustomed to it. Unlike poor Mr. Tennyson who was apparently, initially at least, so taken with Chapel House any nasal incursions went unnoticed, or were ignored, only to prove ultimately overwhelming informing his decision to leave in under three years, indeed, to the point of putting about four miles of seawater between himself and the mainland to boot.

Comments